Alfred Stieglitz

Stieglitz, who was born in 1864 in New Jersey, was a giant of a photographer in late 19th century until his death in 1946. His long term ambition had been to promote photography as a serious art at a time when it was regarded as a technical tool rather than art form. He was an exceptional photographer. He was the editor of a widely respected photography publication called “Camera Work”. He curated exhibitions of photography and promoted modern art from Europe at his gallery, 291 on Fifth Avenue, New York. For example, in 1908 he made use of his connections in Europe to show drawings by Rodin and work by Matisse. He was a founder, with the help of Edward Steichen, of the Photo-Secession movement in 1902 that exhibited work from the gallery. Steiglitz was a non conformist hence the secession as he had little time for the institutional, academic and un-adventurous. The photo Secessionists were really an American part of a much broader movement of Pictorialists.

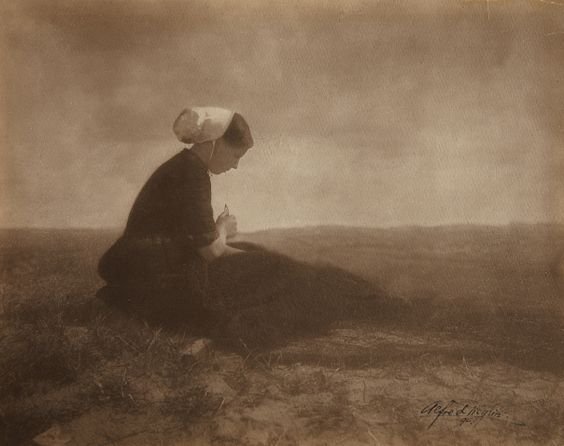

Alfred Stieglitz - Mending Nets, 1894 Holland

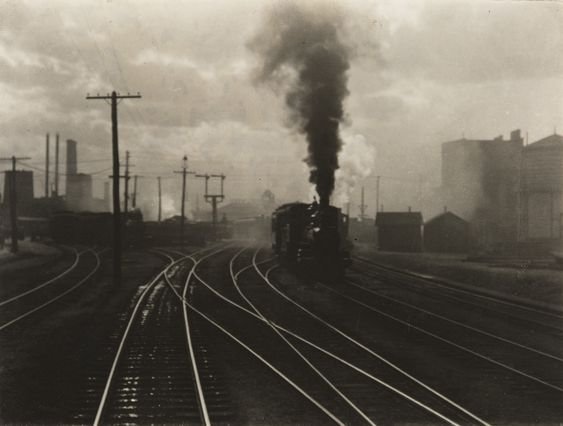

Alfred Stieglitz The Hand of Man 1902

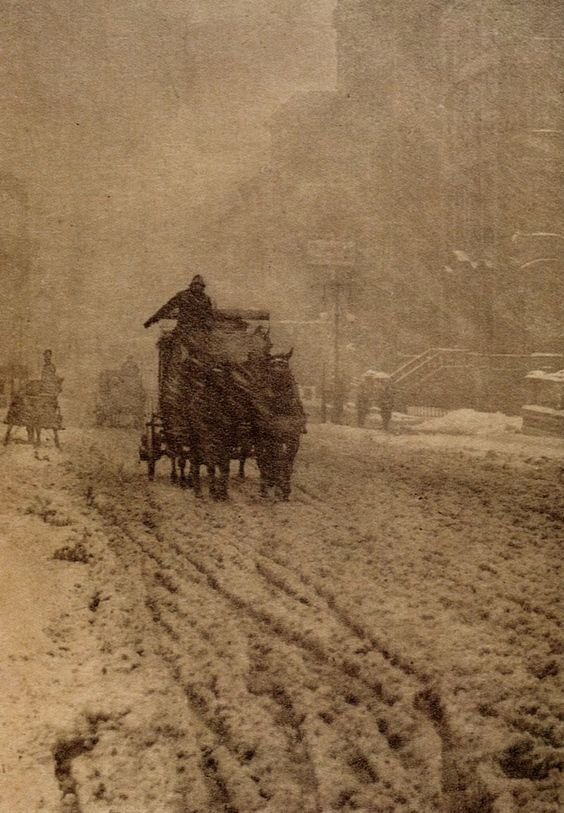

Stieglitz early work was in the Pictorialist manner where photographers tried to mimic painters of the time. Pictorialism flourished largely between 1885 and 1915. Later, he reacted against the widespread attempt by photographers to mimic impressionist or pictorial art. He wanted photography to be accepted as a truthful representation of reality.

Alfred Stieglitz-Winter-Fifth Ave. 1892

“There are many schools of painting. Why should there not be many schools of photographic art? There is hardly a right and a wrong in these matters, but there is truth, and that should form the basis of all works of art.”

Steiglitz not only promoted photography as an art but also promoted the likes of Cezanne, Picasso, Toulouse-Lautrec, Brancusi, and others at 291. Quite uniquely Steiglitz exhibited photography produced by largely unknown Americans with modern art from well known artists from Europe. He really wanted photography to be accepted as art and be seen side by side with paintings and sculpture on an equal footing.

Stieglitz was very much for living in the present.

“I have always been a great believer in today. Most people live either in the past or in the future, so that they really never live at all. So many people are busy worrying about the future of art or society, they have no time to preserve what is.”

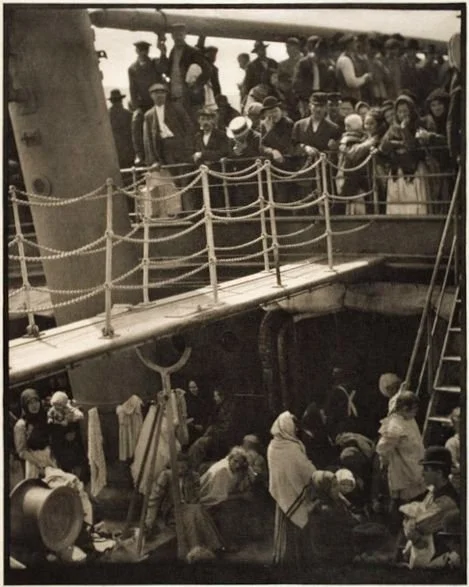

As a photographer, Stieglitz liked to visualise what a photograph could be and wanted to capture the excitement of what he saw. There is a great story behind him taking perhaps his most famous photograph “The Steerage”. In 1907 he was sailing with his first wife and daughter for Europe. By the third day he could no longer stand his surroundings in the First Class section so he walked as far forward as he could until he came to the end of the deck. He stood alone looking down on to the lower decks inhabited by the Second and Third Class. The scene fascinated him and he was drawn to the figure of a young man wearing a straw hat.

“A round straw hat; the funnel leaning left, the stair-way leaning right; the white drawbridge, its railings made of chain; white suspenders crossed on the back of a man below; circular iron machinery; a mast that cut the sky, completing a triangle, I stood spellbound. I saw shapes related to one another - a picture of shapes, and underlying it, a new vision that held me: simple people; the feeling of ship, ocean, sky; a sense of release that I was away from the mob called rich. Rembrandt came into my mind and I wondered would he have felt as I did.”

Stieglitz saw the photo he wanted but did not have his camera with him. He raced to his cabin, raced back with his Graflex and one unexposed plate. He hoped the scene would remain the same. Fortunately the man with the straw hat had not moved, nor had the man in the cross suspenders, and a woman with a child on her lap remained motionless where she had been before. He took the photo and hoped that it would become a picture “based on related shapes and deepest human feeling”. Despite being bored by his First Class surroundings and being drawn into a view of the lower classes, Stieglitz professed only to be concerned with the composition, technical and aesthetics of what he saw. Fortunately, when he developed the photo on his arrival in Europe he achieved what he saw.

“Some months later, after The Steerage was printed, I felt satisfied, something I have not been very often. When it was published, I felt that if all my photographs were lost and I were represented only by The Steerage, that would be quite all right.”

Steiglitz did not refer to his decisive moment, but this is essentially what he had captured in his photograph. He saw what moved him in the composition he visualised and, despite the course of some time, nothing had changed and he was able to produce a remarkable picture.

Pre-visualisation and the decisive moment are really keys to Steiglitz photography as was his desire to express his aesthetic feelings.

“I go out into the world with my camera and come across something that excites me emotionally, spiritually or aesthetically. I see the image in my mind’s eye. I make the photograph and print it as the equivalent of what I saw and felt.”

When taking a photograph, Steiglitz was adamant that he photographed without any preconceptions. He did not consciously seek a meaning before he took a photograph. Only when he was completely satisfied with a photograph did he allow himself to consider its meaning.

“I simply function when I take a picture. I do not photograph with preconceived notions about life. I put down what I have to say when I must… I want solely to make an image of what I have seen, not what it means to me. It is only after I have created an equivalent for what has moved me that I can begin to think about its significance.”

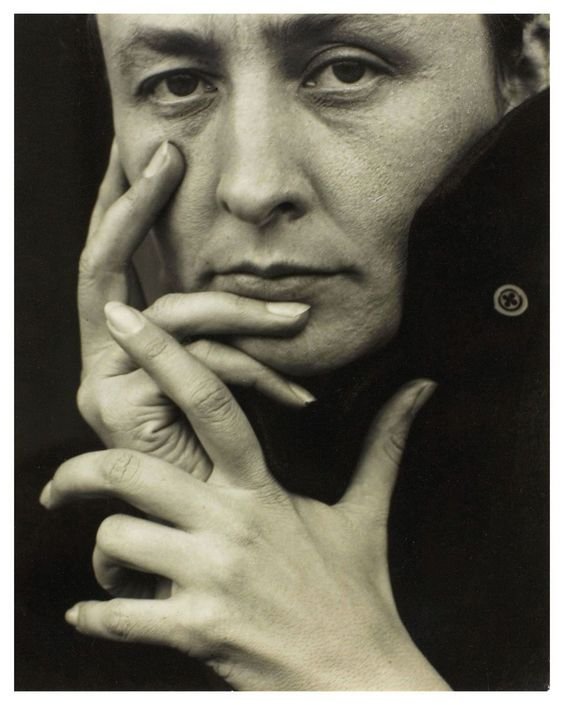

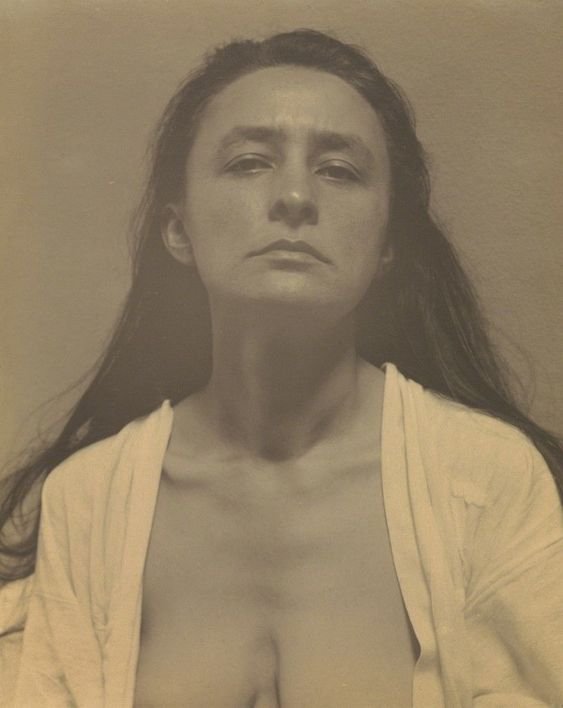

Portrait of Georgia O'Keeffe by Alfred Stieglitz - 1918

Stieglitz met the artist Georgia O’Keeffe in 1916, and was immediately attracted to her. He began to take photographs of her in 1917 at his 291 gallery. By 1924 he has become divorced and marries O’Keeffe. She becomes his muse. In the twenty years from 1917 Stieglitz produces more than 350 portraits of O’Keeffe. These portraits were multifaceted. many were of her nude. Some were only parts of her body such as her hands, and neck.

Stieglitz promoted O’Keeffe’s art with two exhibitions before 291 closed in June 1917. Her paintings encompassed a naturalistic style where truth, honesty and reality predominated. Even when they spent much time apart, O’Keeffe in New Mexico and Stieglitz in New York, they would communicate with regular letters. Between 1915 and 1946 they exchanged over 5000 letters some up to 40 pages long. In the early days of Camera Works there were four issues a year but between 2013 and 2017 there were only six issues in total. Falling subscriptions, supply problems of high quality gravures from Berlin due to the First World War led to the ultimate closure of Camera Works. The final double issue portrayed the future of photography as represented by the work of Paul Strand. The last issues were of straight photography and were very different from the first issues of Camera Works that had been influenced by pictorialism.

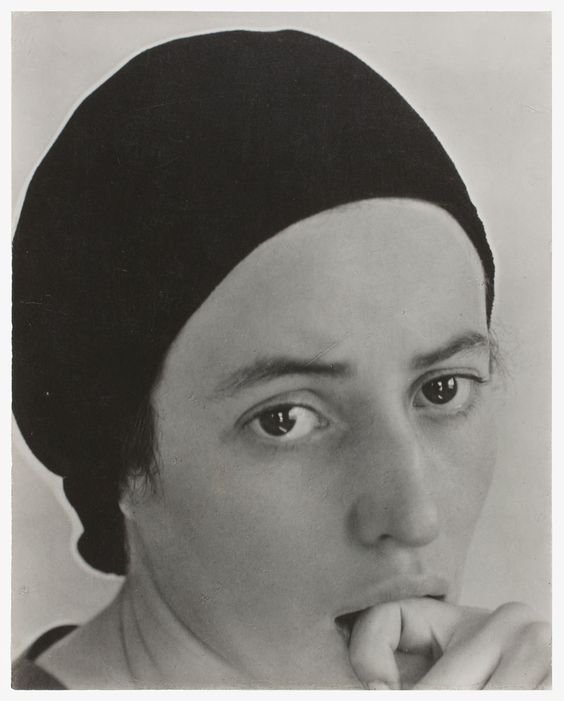

Dorothy Norman, c. 1931

The letters between Stieglitz and O’Keeffe continue during the period they spent increasingly apart. Despite their astonishingly strong attraction toward each other, both had affairs. In 1923, Stieglitz became infatuated with Beck, the wife of Paul Strand. Six years later she would have her own affair with Beck in New Mexico. In 1927, Stieglitz began a much more serious affair with the 22 year old Dorothy Norman. They became lovers over a few years, and they worked together whenever O’Keeffe was not around until Stieglitz died in 1946. Nevertheless, there still remained a strong bond between Stieglitz and O’Keeffe.

“I love you, my wild Georgia O’Keeffe. I’ll never be able to hold you again. So I fear. But I really don’t fear. It looks like snow. Nothing can surprise me, Oh yes, something can. You. Beautiful surprises only.”

Stieglitz to O’Keeffe, 1928